Civilians at the Heart of the Battle

The Bombardments of the Norman Towns

At 0200 hours, for the 1,020 time, since the beginning of the war, the sirens sounded over the city of Caen.

On this occasion, however, it was the start of a vast bombing campaign of the Norman Towns. During the three months preceding 6th June, 22,000 aircraft had already dropped more than 42,000 tons of bombs on 100 railway targets in the Seine Valley, between Le Havre and Paris, in order to isolate the battlefield. In April and May 1944, German fortified positions, listening stations and radar bases were also targeted.

The second phase of the bombing campaign began on the night of 5th-6th June. Between 2330 hours and 0500 hours, more than 1,000 British bombers pounded incessantly the ten coastal batteries between Cherbourg and Le Havre. At dawn, 1,527 American bombers took over, targeting the beaches between Le Havre and the Vire Estuary.

That morning, a dozen urbanised areas and their road and rail infrastructures were also targeted. As at Caen, Flers, Condé-sur-Noireau and Lisieux disappeared in flames. The results were disappointing, low cloud, smoke and flames made it difficult to identify the targets. Towns, such as Caen, were once again bombed. In the area between Pont l’Evêque and Coutances, a dozen towns were targeted by the US 8th Air Force: Pont L’Evêque, Lisieux, Vire, Condé-sur-Noireau, Flers, Coutances and Saint-Lô were bombed in order to prevent the German forces advancing towards the beaches. On the morning of 7th June, the outcome was far from satisfactory for the Allies but, with enormous losses for the civilian population, 2,200 were killed in the raids.

The Bombing of Caen

In Caen, the bombing raids targeted the four bridges over the River Orne to prevent the Germans from advancing towards the sea.

The Decaen Barracks and the area around the railway station at Caen were very heavily bombed at 0700 hours. Later, at 1330 hours, six squadrons of American B24 bombers dropped an additional 200 tons of bombs on the city. The Saint-Jean district, between the castle and the River Orne, was completely destroyed. Over 10,000 inhabitants, out of a total of 62,000, fled the town. The districts of Vaucelles, la Place de la Mare, le Gaillon, la route de la Délivrande, la rue Saint Pierre and the castle itself were all seriously damaged. The victims and the wounded were taken to the Bon Sauveur and Miséricorde hospitals while the refugees made their way to shelters at the Lycée Malherbe and the town hall, others chose to take shelter in the caves at Fleury-sur-Orne. At 1630 hours, another raid destroyed the ancient district of Saint-Etienne. A third raid, at 2130 hours, destroyed the Saint-Julien and Saint-Louis areas. By the evening of 6th June, 300 dead had been pulled from the ruins but, the bridges over the River Orne were still intact.

Executions at Caen Prison

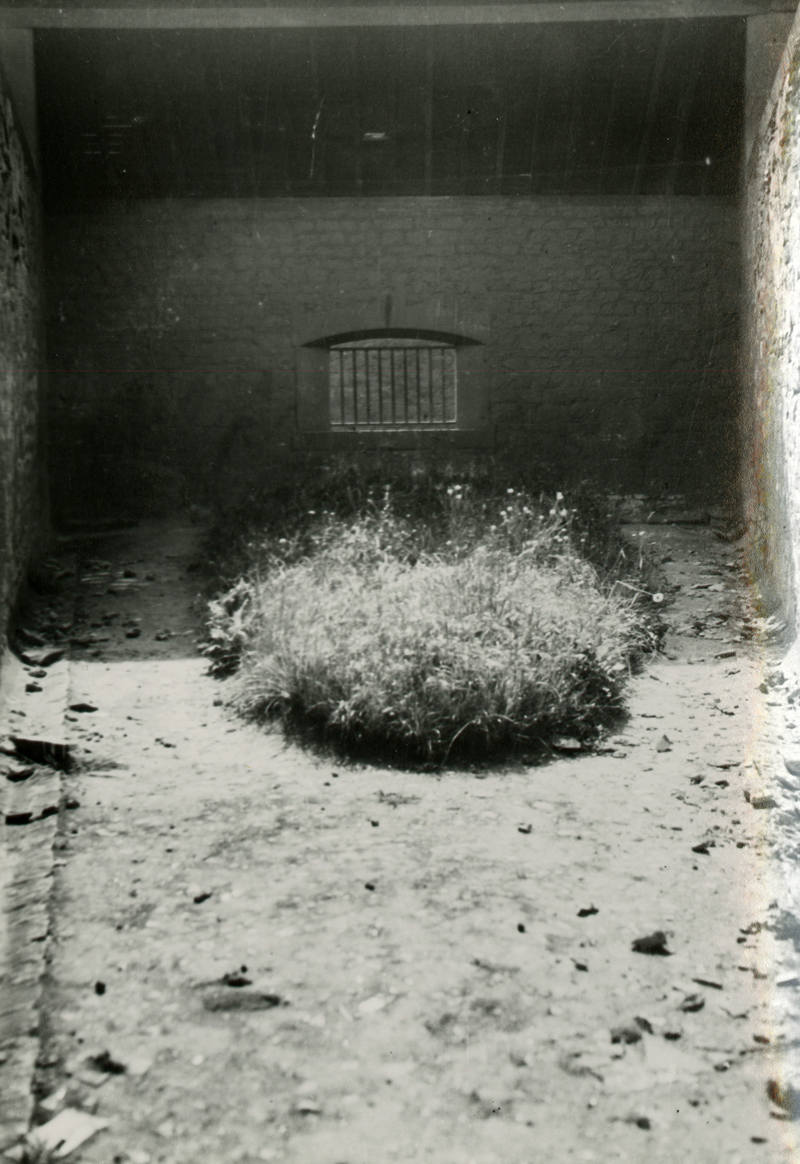

On 6th June, after learning of the Allied landing in Normandy, the head of the Gestapo in Caen ordered the execution of 87 inmates in the grounds of the local prison. Their remains have still not been located to this day.

From December 1943, German repression increased in Normandy. More than 200 members of the Resistance had been arrested by the Gestapo. On learning of the landings, the commander of the German section at Caen prison carried out the orders he had received in case of an alert, to send all inmates, held by the Gestapo, to Germany to avoid them falling into Allied hands. As for those who were to be judged by the Wehrmacht, they were deported or freed depending on the accusations against them. The Feldkommandatur attempted to carry out Major Hoffman’s orders but the destruction at Caen station had made the railway infrastructure unusable. The Germans did not even have enough vehicles, nor the necessary troops to carry out the order in complete security. Towards 0800 hours, Harald Heyns, the Caen Gestapo chief, visited the prison and informed Hoffman of the decision to execute the prisoners immediately. From morning to evening, in groups of six, 87 prisoners were executed in the prison courtyard. Women were also not safe, 20 female inmates were transferred to Fresnes. The remains of the executed men were immediately covered in lime and interred in hastily dug pits in four of the inner courtyards. At the end of June 1944, the Germans returned to the prison to remove the remains and take them elsewhere. It remains a mystery to this day where they were reburied.

The German Reaction

The German Reaction to the Airborne Operations

At midnight, General Feuchtinger, commander of 21st Panzer stationed to the south east of Caen, learnt of the Allied landings. On Rommel’s orders, he could take no action, he did, however, put his division on alert before leaving Paris to return to Normandy. At 0110 hours, General Speidel, Rommel’s Chief of Staff at his headquarters at la Roche-Guyon, received the first reports of a landing while, at Saint-Lô, General Marcks was made aware of the airborne landings to the east of the River Orne.

At 0130 hours, 7th German Army was put on alert. General Richter, commander of 716th Infantry Division, responsible for the coastal defenses between the Rivers Orne and Vire, ordered 21st Panzer to attack 6th Airborne Division’s landing zone but, there was no reply to his order.

At 0200 hours, General Bayerlein, the commander of the Panzer Lehr Division, based in the region of Le Mans, was informed of the situation at his headquarters at Chartres.

At 0230 hours, Admiral Hennecke, at his headquarters at Cherbourg, informed 7th Army headquarters that parachutists had landed in the vicinity of the Crisbecq-Saint-Marcouf Batteries. General Pemsel, Chief of Staff of 7th Army, at his headquarters in Le Mans, was also informed of airborne landings and contacted Rommel’s headquarters to inform his Chief of Staff, General Speidel that a landing was imminent. The 12th SS Panzer Division was subsequently put on alert.

The headquarters of the Western Naval Group in Paris ordered a reconnaissance to be carried out at sea. Patrol boats put to sea from Cherbourg but, had to return due to the bad weather. Off the coast of Dieppe, other naval craft were also forced to return to port.

Shortly before dawn, at 0400 hours, von Rundstedt envisaged, out of caution, to move two armoured formations towards Normandy: the Panzer Lehr and 12th SS Hitler Youth Divisions. To do this, he requested permission from the Supreme Command in Berlin, Hitler’s reply did not arrive until ten hours later, much too late.

The Armoured Advance

It was only from 0630 hours, when American troops had started landing on Utah and Omaha Beaches that the first orders to attack were carried out by 21st Panzer Division. General Feuchtinger ordered his men to attack 6th Airborne Division established in the bridgehead around the Orne to the north east of Caen. At 0700 hours, von Rundstedt was refused by the High Command of the Wehrmacht (OKW) to deploy the panzer divisions stationed in Normandy. The 12th SS Panzer Division, however, without waiting for orders, was regrouping in the Bernay-Vimoutiers-Lisieux sector.

Only at 0830 hours, did Colonel von Oppeln-Bronikowski’s panzer regiment advance along the east bank of the Orne before counter-attacking the British forces for the first time. At 1000 hours, Feuchtinger received new orders to stop the movement of his forces east of the Orne in order to move them further west to support the forces defending Caen. At 1500 hours, Colonel von Oppeln-Bronikowski’s 40 tanks crossed Caen and exited to the north as his armour prepared to counter-attack, to push the British back into the sea. As they headed towards the coast, his units were forced to take cover in the Lébisey wood above Periers-sur-le-Dan (five kms north of Caen) due to stout resistance from three squadrons of the Staffordshire Yeomanry.

While 12th SS Hitler Youth Division was receiving its orders to head towards Caen in the afternoon, another division, the Panzer Lehr, was hurriedly preparing to move towards the front in Normandy. Many of the division’s tanks had been loaded onto trains to be shipped to Poland. The divisional commander, General Bayerlein, had received a countermand, however, ordering his forces to head for Normandy. His request to advance in darkness was refused and while his armour assembled in daylight the division was attacked incessantly by the Allies. The division had lost 40 vehicles by the evening of 6th June, before it had even been in action.

Berchtesgaden on 6th June

At Berchtesgaden, Hitler, as was usual, retired to bed late, at 0300 hours, without having been informed of the situation on the front in Normandy.

Hitler was woken at 1000 hours and was immediately informed of the situation. During the daily midday conference, he was given the first reports established by the Intelligence Service. Hitler, aware that numerous Allied divisions had not been engaged in the battle and were still stationed in Scotland and the south-east of England, concluded that the landings were a diversion and congratulated Jodl for having prevented von Rundstedt from using, prematurely, his reserve forces. Hitler’s meeting with Rommel had been cancelled at the last moment as Rommel had been informed, at 0700 hours, of the landings by his Chief of Staff while at home at Herrlingen near Ulm. Towards 1430 hours, the “Fuhrer” finally authorised the movement of units of 7th Army, Panzergruppe West, Army Group B (Rommel) and the High Command in the west (von Rundstedt). Hitler also ordered 12th SS Division garrisoned at Argentan and Panzer Lehr, positioned near Le Mans, to advance towards the coast. He was unaware that the Hitler Youth Division had already started to advance without having received the necessary orders.

Hitler expressly forbade any movement of 15th German Army, which was positioned in the north of France, as he was totally convinced that the bridgehead forming in Normandy was a diversion to hide “real” landings which were imminent in the following days.

Assessment of 6th June

Everywhere along the coast, the German defenses of the Atlantic wall failed to resist. On the evening of 6th June, General Richter’s 716th Division had lost 3,000 men out of a compliment of 7,800 troops. That evening, a conference was organised at General Richter’s headquarters near Caen.

Amongst the participants were General Feuchtinger (21st Panzer) and Kurt Meyer, commander of 25th Panzer Grenadier Regiment of 12th SS who had been ordered to attend by General Witt. The meeting’s objective was to prepare a powerful counter-attack. The conditions for such an operation, however, could not be met, as a large part of 12th SS was only just starting to advance from the Argentan sector and the Panzer Lehr was not even near the front. The counter-attack, late on 6th June, was therefore postponed. For the commanders of 21st Panzer and 716th Infantry Divisions the plan was clear, the following days counter-attack must reach the coast and push the Allies back into the sea. While waiting, an order was given for the 4,000 men of the Heintz Combat Group of 275th Infantry Division, based in Southern Brittany, to be moved by rail to Normandy and the Cotentin Peninsula. Once on the front in Normandy, these important reinforcements would be attached to the 17th “Gotz von Berlichingen” Panzer Grenadier Division.

Airborne Operations

British Airborne Assault

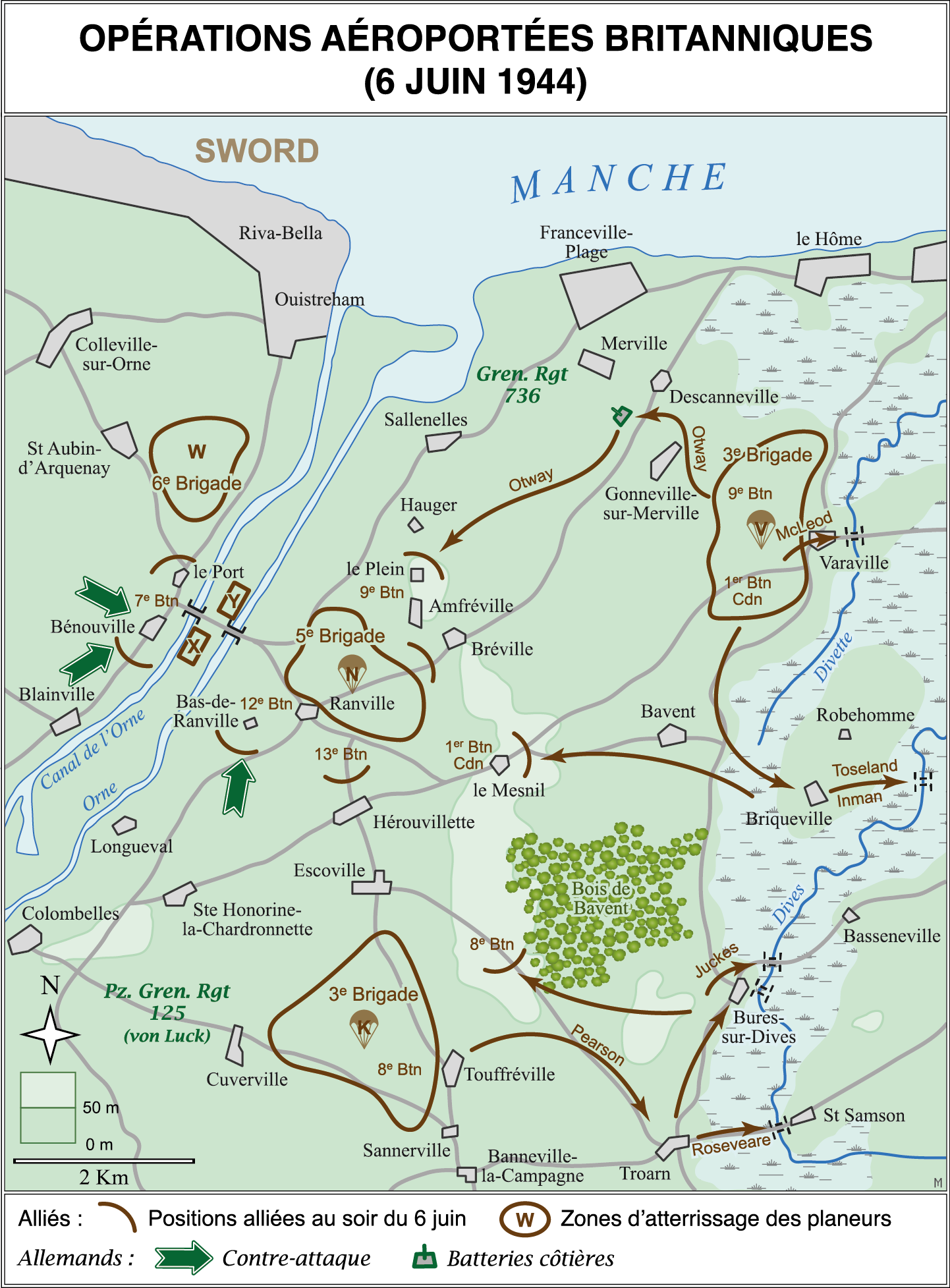

The Objectives

The German forces had flooded the ground to the east of Sword Beach as they had also done further west in the Utah Beach sector. It was into this area that the Allies chose to drop General Gale’s 6th Airborne Division with the principal objective of protecting the left flank of the landings from counter-attacks by 15th German Army, during and after D-Day. In order to carry out its mission successfully, the airborne forces had to seize the Merville Battery, destroy five bridges over the Rivers Dives and Divette at Troarn, Bures, Robehomme and Varaville and seize intact the bridges at Bénouville and Ranville. The latter operation would be the most daring and difficult to carry out, the mission was given to D Company, 2nd Battalion of the Ox and Bucks commanded by Major John Howard.

The “Coup de Main” Operation

Six glider aircraft, which had taken off at 2300 hours on 5th June, were towed across the Channel and released above the town of Cabourg. Transported in the gliders were 180 men commanded by Major John Howard (D Company, 2nd Battalion of 6th Airlanding Brigade). The aircraft landed to the west of the River Orne at 0016 hours. One soldier from the company was killed and several were wounded. Gliders N°s 1, 2, 3, 5 and 6 landed with great precision by the Ranville and Bénouville Bridges but, N° 4 glider landed 13kms from its objective near the Dives at Périers-en-Auge. This was the start of the “Coup de Main” Operation.

The assault on the Bénouville Bridge began at 0020 hours. The German sentries were totally surprised but, during the attack, Lieutenant Brotheridge was mortally wounded in the neck. He was almost certainly the first British soldier killed on D-Day. The explosive charges which were thought to have been placed on the bridge were absent and were later found by Lieutenant Smith’s platoon near the bridge.

At Ranville, the undefended swing bridge, 400 metres from the Bénouville Bridge, was taken by two other sections of the Ox and Bucks which had landed in gliders N°s 5 and 6. In the absence of Captain Priday who should have commanded the attack, but had landed in the lost N°4 glider, the assault was led by Lieutenant Fox’s platoon reinforced by Lieutenant Sweeney’s platoon. Casualties sustained in the “Coup de Main” operation were 2 killed and 14 wounded. After having sent the coded signal “Ham and Jam”, Howard prepared the defenses and waited for the arrival of the reinforcements from 7th Parachute Battalion which was due to land at 0050 hours.

Major John Howard enlisted in the army in 1932 at 19 years of age prior to joining the police force in Oxford in 1938. Recalled in 1939, he was attached to glider borne forces and took command of D Company of 2nd Battalion Ox and Bucks. Several weeks prior to D-Day, Howard was designated to lead the mission of seizing the bridges at Ranville and Bénouville which would facilitate 3rd Infantry Division’s advance towards Caen. Howard supervised the training and prepared the plans himself. On 6th June 1944, John Howard became part of the Pegasus Bridge legend; he subsequently led his company throughout the Battle of Normandy until September 1944. Howard was seriously injured in a traffic accident in England in November 1944 and was invalided out of the Army in 1946. He subsequently worked for the Civil Service until his retirement in 1974. John Howard died in 1999.

2.4

Den Brotheridge commanded 25 Section of D Company of 2nd Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry which was given the mission of seizing the bridges at Bénouville and Ranville. Brotheridge flew into Normandy, along with his commanding officer, Major John Howard, in Glider N° 1 which landed at 0016 hours. The landing was very violent but extremely precise, less than 47 metres from the bridge which enabled Brotheridge to immediately cross the bridge in the direction of a German Machine gun nest. It was at this very moment that he was mortally wounded in the neck. Brotheridge was 29 years of age and left a pregnant wife in England. Den Brotheridge lays today at Ranville municipal cemetery.

The Airborne Landings

At 0020 hours, 60 parachutists of 22nd Independent Pathfinder Company landed on the drop zones Ranville, Varaville and Touffreville. The company’s mission was to mark the landing zones with radio beacons which would be necessary to guide the gliders and the aircraft, transporting material, over the zones.

Thirty minutes after the zones had been marked; more than 2,000 men of 5th Brigade (7th, 12th and 13th Battalions) were dropped north of Ranville along with 730 containers of equipment. The parachute battalions had to clear Drop Zone N prior to the arrival, en masse, of the brigade’s gliders at 0330 hours. The drop was widely dispersed with 16 men killed, 82 wounded and 430 paras unable to find their units.

Simultaneously, parachutists of 1st Canadian Battalion (less C Company which had already jumped as Pathfinders at 0030 hours) and 9th Battalion of 3rd Brigade dropped on Drop Zone V between Varaville and Gonneville. Widely dispersed and lost, 150 men, commanded by Colonel Otway, took more than four hours to regroup before heading for their objective, the Merville Battery.

The men of Colonel Pearson’s 8th Battalion (3rd Brigade) landed at 0050 hours near Ranville and Touffreville. After regrouping, they were to head towards the bridges at Bures and Troarn and destroy them.

Following the arrival of the parachute battalions, the equipment arrived. Shortly after 0100 hours, three gliders out of a planned six (the others crash landing on other zones) arrived on the Touffreville landing zone carrying jeeps, heavy weapons and explosives. While 13th Battalion arrived at the Ranville crossroads with the mission of destroying, with explosives, the Rommel’s “asparagus” on Drop Zone N, another group of paras entered the village, at 0230 hours, and Ranville became the first village to be liberated.

Shortly afterwards, at 0300 hours, 7th Battalion of 5th Brigade landed at Ranville in order to reinforce the troops at the Bénouville Bridge. The battalion immediately took up defensive positions in Bénouville and in the hamlet of Le Port. Finally, the commanding office of the airborne forces, General Gale, landed at Ranville by glider in the third assault wave which brought in heavy equipment and the divisional headquarters. At 0330 hours, Ranville had been secured and Gale made his way to his headquarters at the Chateau du Hom.

Before day break, the eastern flank of the landing coast was firmly held. Operation Tonga which began at midnight and terminated at dawn was an outstanding success, 74 gliders landed as planned, 4,330 men and 1,200 gliders were on the ground by 0520 hours.

The final operation in this sector, Operation Mallard, took place in the evening between 2030 hours and 2100 hours when 250 additional gliders landed at Ranville, Bénouville and Saint-Aubin-d’Arquenay carrying 2,800 troops of 6th Airlanding Brigade.

By the evening of 6th June, 1,120 gliders had landed to the east of the Orne. More than 9,000 British troops had arrived in the sector to hold, at all costs, the bridgehead until the liberation of Caen.

Richard Nelson Gale was a veteran of the Great War and had fought on the Somme. In 1941, he was promoted to brigadier and was given the mission of creating 1st Parachute Brigade. He was promoted again in 1943 to command 6th Airborne Division. Gale organised and intensively trained his elite force to make them ready for the landings in Normandy. On 6th June 1944, he landed in the third wave of gliders before establishing his headquarters at Ranville and commanded the bridgehead, formed by the paras and commandos, until the beginning of Operation Paddle on 15th August 1944. He returned to England after the Battle of Normandy and subsequently, after the war, commanded in the Mediterranean and in Germany and was appointed Aide de Camp to the Queen in the 1950s. Richard Gale died in 1982, the emblematic figure of 6th Airborne Division.

The Destruction of the Bridges over the Dives and Divette

To the east of the Orne, the destruction of the bridges was primordial in order to slow the arrival of German reinforcements and permit a successful landing on Sword Beach.

C Company of 1st Canadian Battalion (3rd Brigade) commanded by Major Macleod landed to the west of Varaville shortly before 0030 hours and 30 minutes before the main force. The company’s mission was to clear the landing zone, seize a bunker at Varaville and destroy the bridge over the Divette. Badly marked and covered by German gun fire, the drop zone was difficult for the parachutists to identify, many of them getting lost once on the ground. Nevertheless, Macleod was able to assemble some of his men and headed towards Varaville. In the combat with the Germans, entrenched in the chateau, Macleod and several of his men were killed. The paras had to abandon their position before 40 German troops finally surrendered at 1030 hours. However, Varaville was not liberated immediately as the paras were forced to withdraw towards Le Mesnil under intense German artillery fire. Despite this set back, C Company had successfully destroyed the Varaville Bridge. B Company had a similar mission to carry out at the Robehomme Bridge.

After having regrouped on the ground, the unit advanced with difficulty in the marshland in search of the River Dives Bridge which was finally reached and destroyed at 0830 hours. Robehomme was immediately occupied by the Canadians who took up position in the church tower which was ideal for observing the surrounding valley.

To the south of Robehomme, the Bures and Troarn Bridges were to be destroyed by 8th Battalion which was also widely dispersed in the drop. With the little weapons and explosives which could be assembled, 120 paras regrouped, to the west of Touffreville, and set out towards Bures at 0345 hours, reaching the two metal bridges shortly before 0600 hours. At 0630 hours, the Sappers had placed the charges on the bridges and they collapsed into the Dives at 0715 hours. Troarn, which was occupied by over 200 German troops, was the next objective. Two hours previously, Major Roseveare, after having entered Troarn in a Jeep towing a trailer full of explosives, blew a 5 metres gap between the pillars of the bridge. However, the approaches to the village were occupied by armour of 21st Panzer Division which prevented the parachutists from entering the village to complete the total destruction of the bridge.

Troarn was eventually liberated and the bridge completely destroyed at 1500 hours.

By this time, all the bridges over the Dives had been destroyed. The parachutist’s mission had been completely successful.

Ranville, First Village to be Liberated by the British

The village of Ranville, to the east of the swing bridge, renamed “Horsa Bridge”, which had been taken without difficulty by Major Howard’s men, was liberated at 0230 hours by men of 5th Parachute Brigade. The men of 13th Lancashire Battalion had no difficulty in clearing the town centre of any German resistance allowing General Gale to set up his divisional headquarters at the Chateau du Hom an hour later. However, later in the morning, the paras had to fend off a German counter-attack at the Bas de Ranville by the Major Von Luck’s regiment of 21st Panzer Division. The majority of the men killed on 6th June to the east of the Orne were interred that very evening around the church at Ranville municipal cemetery. Today, 2,564 soldiers, 2,152 of them British, lay at Ranville War Cemetery which is proud to claim to be the first village liberated.

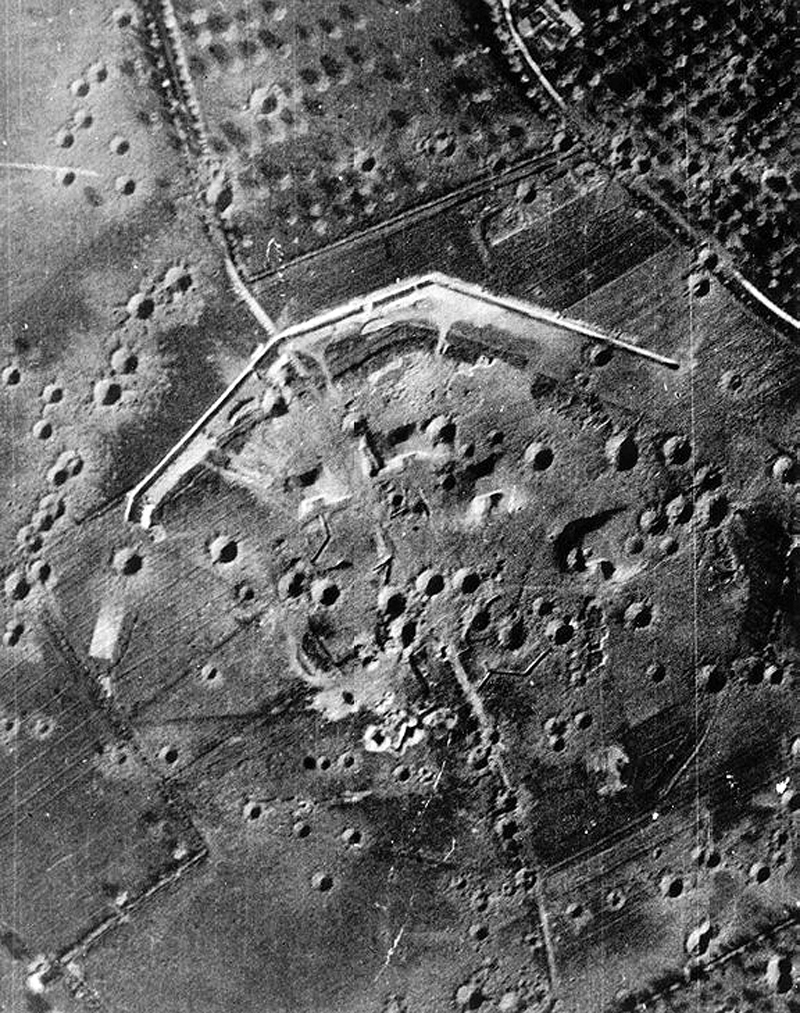

The Merville Battery Assault

Constructed inland to the south of the village of Merville, the battery consisted of four concrete bunkers housing 150 mm guns and with a garrison of 150 men.

The battery posed a major threat to the landings on Sword Beach. The assault was planned for the night preceding D-Day and was to be carried out by Lieutenant Colonel Otway’s 9th Parachute Battalion. Otway’s situation was dire, at 0100 hours, he was only able to assemble 150 men at Varaville, and they were short of arms (one machine gun and several Bangalore torpedoes), out of an effective of 550 parachutists, many had become lost following the drop. The three gliders which should have landed within the battery’s perimeter failed to do so, two of them flew over the battery alerting the German defenses. Despite these setbacks, Otway carried out the assault at 0430 hours by leading his men, in four groups, towards the four casemates. The assault was brief but ferocious; Otway lost half his men in capturing the guns which were of a smaller calibre (100mm and not the 150 mm as expected). Colonel Otway and his men had to evacuate the battery at 0500 hours before the naval barrage commenced from HMS Arethusa positioned off the coast. Despite the heavy losses and the little risk the battery posed to the landings on Sword Beach, the assault on the Merville Battery was one of the major feats of arms of D-Day.

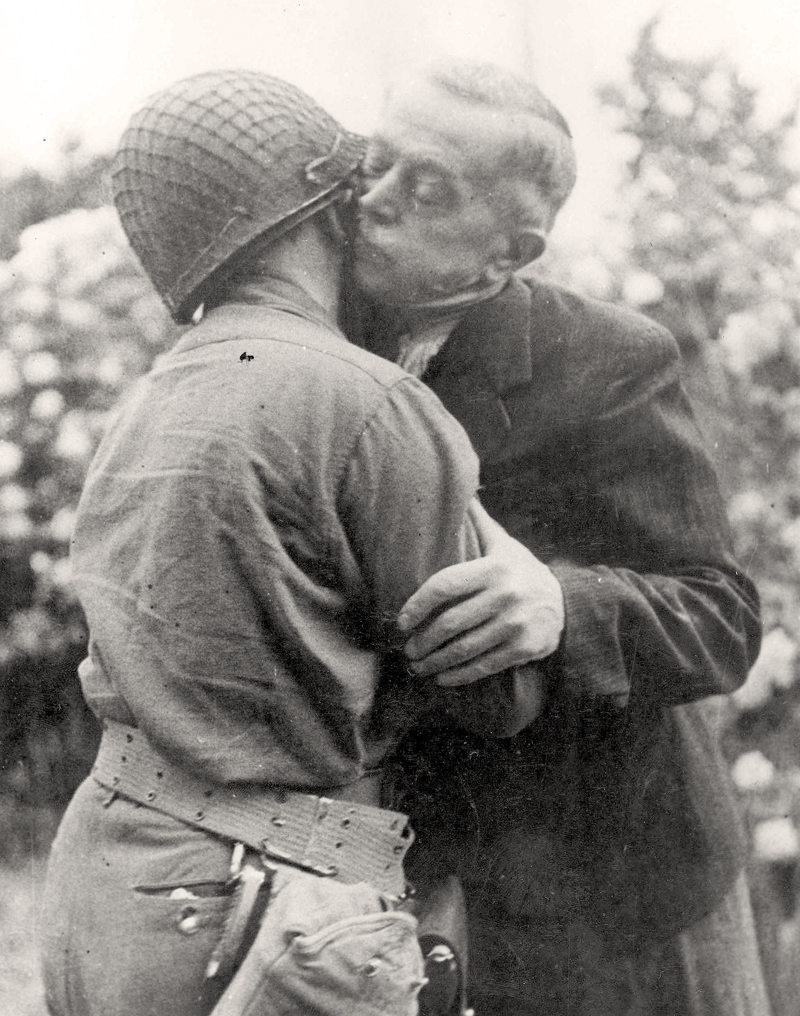

The Junction between the Airborne Forces and the Commandos of 1st Special Service Brigade

The 1st Special Service Brigade, after having landed in several waves on Sword Beach, advanced, crossing Colleville and headed on towards Saint-Aubin-d’Arquenay.

The Anglo-French N°4 Commando, meanwhile, was detached from the brigade to liberate Ouistreham. The fields crossed by the brigade were full of 6th Airborne gliders and under isolated German gunfire. The troops arrived at the swing bridge, led by bagpiper Bill Millin, to forewarn the paras of the arrival of the commandos. The junction was finally made at midday at the Café Gondrée where Major Howard and Lord Lovat greeted each other. The commando force then continued its advance crossing Pegasus Bridge under enemy fire, advancing further into the bridge head towards Ranville and Amfreville.

ENT.2-11

Bill Millin spent the first 12 years of his youth in Canada, where he was born, before returning to Scotland in 1934. Ten years later he would be the only bagpiper to land on D-Day as the personal piper to Lord Lovat, commander of 1st Special Service Brigade. On 6th June 1944, Millin, a veteran of the North African and Italian Campaigns, played “Highland Ladies”, “The Road to the Isles” and “Rawon Tree” as he made his way from Colleville to Pegasus Bridge before being ordered by Lovat to play a specific tune to alert Major Howard of the arrival of the commandos. The famous “Blue Bonnets over the Border” as they advanced into Benouville followed by “March of the Cameron Men” leaving Pegasus Bridge.

Bill Millin frequently returned to the sites of his wartime exploits before his death in 2010.

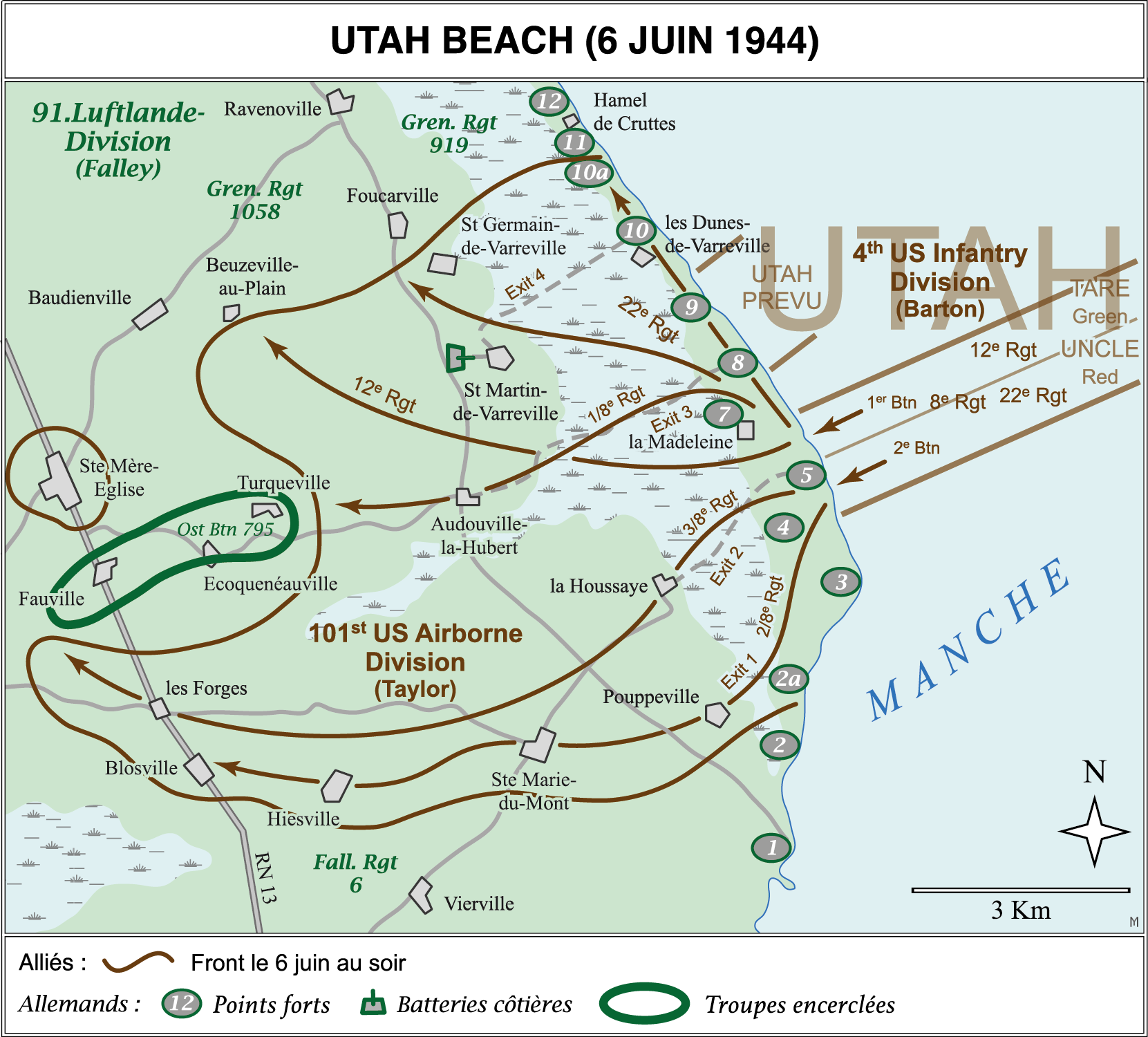

Airborne Operations

The American Airborne Assault

In order to capture the port of Cherbourg, in December 1943, the Allies added an additional beach, Utah, to the west of the Baie des Veys. To protect this sector, two airborne divisions were to be dropped at Saint-Marie-du-Mont and Sainte-Mère-Eglise. The airborne assault by 82nd and 101st Airborne Divisions, commanded by Generals Ridgeway and Taylor, would land the night before the seaborne landings to prevent German counter-attacks towards the beach. The paras had to control the four access roads leading to Utah Beach, destroy the bridges over the River Douve and form a bridgehead to the west of the River Merderet and occupy Sainte-Mère-Eglise.

Operations began at 0015 hours with the drop of 260 Pathfinders transported aboard 40 aircraft. The men had the mission of marking the landing zones for the parachutists and the gliders. Frank Lillyman, the commander of 101st Airborne Division Pathfinders, was almost certainly the first American soldier to step foot in Normandy.

On 6th June 1944, Frank Lillyman was serving in 502nd Regiment and commanded the pathfinders of 101st Airborne Division which had the mission of marking the parachute and glider landing zones. At 0015 hours, Frank Lillyman was the first to jump from the first aircraft. He was repatriated to England after being wounded but returned to Normandy later in the battle.

ENT.2-14.1

The 101st Airborne Assault

Between 0100 hours and 0200 hours, 900 C47 Dakota aircraft dropped the men of 82nd and 101st Airborne Divisions.

The 101st landed in the Sainte-Marie-du-Mont Sector. General Taylor, commander of the 6,900 paras of the division, was the first American general to land in France. The division, formed in the summer of 1942, was composed of three regiments (501st, 502nd and 506th) and received it’s baptism of fire that morning. The pilot’s lack of experience, the anti-aircraft fire and the flooded marshland led to a wide drop and heavy losses.

Colonel Moseley’s 502nd Regiment dropped on Zone A (Turqueville) before advancing towards the Saint-Martin-de-Varreville Battery. After breaking a leg in the jump, Moseley relinquished command to his deputy, Colonel Michaelis. During a drop which was largely inaccurate, Colonel Cassidy who commanded the regiment’s 1st Battalion was only able to assemble 205 men to secure the Foucarville-Beuzeville-au-Plain sector. At 0115 hours, units of 501st and 506th were badly mis-dropped on Zones C and D in the area of Hiesville, Saint-Come-du-Mont, Sainte-Marie-du-Mont and Vierville. Led by General Taylor, two groups set out towards the exits leading from Utah and Pouppeville.

At 0130 hours, Colonel Johnson, commander of 501st Regiment, was dropped to the south of Angouville-au-Plain. Regrouping 150 men, he advanced in the direction of the bridges over the Douves.

ENT.2-15

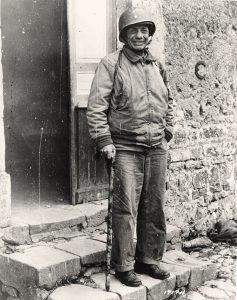

General Taylor, the First American General to Land in Normandy

Maxwell Davenport Taylor, a student of West Point, was promoted to general rank in 1942 at the age of 41. One of his missions was to assist General Ridgeway in the conversion of 82nd Division into an airborne unit in 1942. After having participated in the Italian Campaign in 1943, Taylor was designated by Eisenhower in 1944 to command 101st Airborne Division. He jumped into the Cotentin Peninsula shortly before 0100 hours and led the men, he had assembled, in combat throughout the day. He remained with 101st until it was withdrawn from combat at the end of June 1944. After the war, he commanded 8th American Army in Korea before taking on an important political role during the Cold War. Maxwell Taylor died in 1987.

The 82nd Airborne Assault

The 82nd Airborne Division was a veteran division with accumulated experience of the North African Campaign in 1942 and Sicily and Italy in 1943. Composed of four regiments with a total compliment on D-Day of 7,500 men of which 6,400 were to be deployed in the Cotentin Peninsula from 377 aircraft and 52 gliders.

Three regiments of 82nd, 505th, 507th and 508th were dropped at 0200 hours. The objective was well established, to seize the main road at Sainte-Mère-Eglise and the bridges over the Merderet.

Colonel Vandervoort’s 505th Regiment was dropped on Zone O before taking up positions at Neuville-au-Plain, to the north of Saint-Mère-Eglise. Despite breaking a leg in the jump, Colonel Vandervoort led his troops in resisting repeated counter-attacks by the German 91st Division. Several men were dropped directly into the town centre at Sainte-Mère which was defended by the German forces. Amongst them, Private John Steele, who was injured when his parachute snagged on the church tower. Steele feigned death for several hours before being taken down from the church by a German soldier.

Colonel Millett’s 507th Regiment and Colonel Lindquist’s 508th Regiment were widely dispersed in the drop to the west of the Merderet on drop zone N while the commander of 2nd Battalion of 508th Regiment, Colonel Shaney, assembled 300 men near Picauville and headed for Hill 130, the regiment’s assembly point.

Private John Steele, originally from Illinois, jumped into the village of Sainte-Mère-Eglise while serving with 505th Regiment of 82nd Airborne Division. He finished his descent into Normandy on the church steeple at 0400 hours. Wounded by shrapnel, Steele feigned death for over two hours to avoid being shot. He was finally detached from the steeple by a German soldier and taken prisoner early on D-Day.

Steele, after having recovered from his experience, escaped three days later and rejoined his unit and later participated in the liberation of Sainte-Mère-Eglise. The events surrounding John Steele are some of the most iconic images of the movie “The Longest Day”.

The Paras in Action

Despite the confusion on the ground, which led to few American units being immediately operational, the situation for the German forces was far worse due to the drops being widely dispersed, creating numerous small American units on the ground. At 0400 hours, Colonel Cole (502nd Regiment) arrived at his objective with 120 men. He could only note the destruction of the Saint-Martin gun battery which had been destroyed by Allied bombing. Cole, therefore, led his men in the direction of the Utah Beach exits where he made the junction with the first elements of 4th Infantry Division in the early afternoon. Sainte-Mère-Eglise was occupied at 0430 hours by 250 parachutists led by Lieutenant Colonel Krause, commander of 3rd Battalion of 505th Regiment.

In the meantime, General Pratt, deputy commander of 101st Airborne Division, was killed when his glider crashed landed.

Sainte-Marie-du-Mont was liberated in the afternoon by parachutists of 501st and 506th Regiments (101st Airborne) led by Captain Patch who was forced to repel a counter-attack by 6th German Parachute Regiment commanded by Colonel von der Heydte.

ENT.2-19

Sainte-Mère-Eglise is as well-known as it is today as much for the events portrayed in the film as for the combat which took place there in the early hours of 6th June. While paras of 101st were mistakenly dropped into the town square, shortly before 0100 hours, the inhabitants and the German troops were attempting to extinguish a fire which had broken out near the church. Many paras from 101st and 82nd Airborne were killed immediately, before they had even landed. Suspended for over two hours from his parachute, which had snagged on the church tower, John Steele became, after the war, the symbol of the courage and sacrifice of the American paras on 6th June. The village was finally liberated at 0430 hours by Lieutenant Colonel Krause and his men. However, the junction with the troops arriving from Utah was only made on the following day. Since the war, Sainte-Mère-Eglise and Ranville, liberated by the British at 0230 hours, have disputed the title of first village liberated in France.

The Bridges over the Douve and the Merderet

The paras of 101st Airborne advanced towards the bridges over the Douve. At 0430 hours, a small group of men, led by Captain Shettle of 3rd Battalion, 506th Regiment, set up positions on the west bank opposite the Germans defending the approaches to Carentan. Thirty minutes later, Colonel Johnson (501st Regiment) along with 50 men arrived at their objective, the lock at la Barquette across the Douve estuary north of Carentan.

The drops to the west of the Merderet were the least successful of any in this sector. Several days were necessary for the men of 82nd Airborne to rejoin their units. Despite this handicap, General Gavin, with men from 507th and 508th Regiments, seized the bridges over the Merderet, notably at La Fière, shortly after 1100 hours.

Assessment of 6th June

More than 13,000 parachutists of 82nd and 101st Airborne, transported in over 1,000 aircraft, including 100 gliders, landed between midnight and 0300 hours. Affected by adverse weather conditions and anti-aircraft gun fire, the drop was imprecise, 75% of the men landed far from their drop zones, many in the flooded marshland, seriously hampering the assembly of the various units. The first junction to be made between the paras and 4th Infantry Division, arriving from Utah Beach, was at Pouppeville in the early hours. Despite a failure to have carried out all the missions successfully, the protection of the infantry landing on Utah Beach was assured by dawn on 6th June.

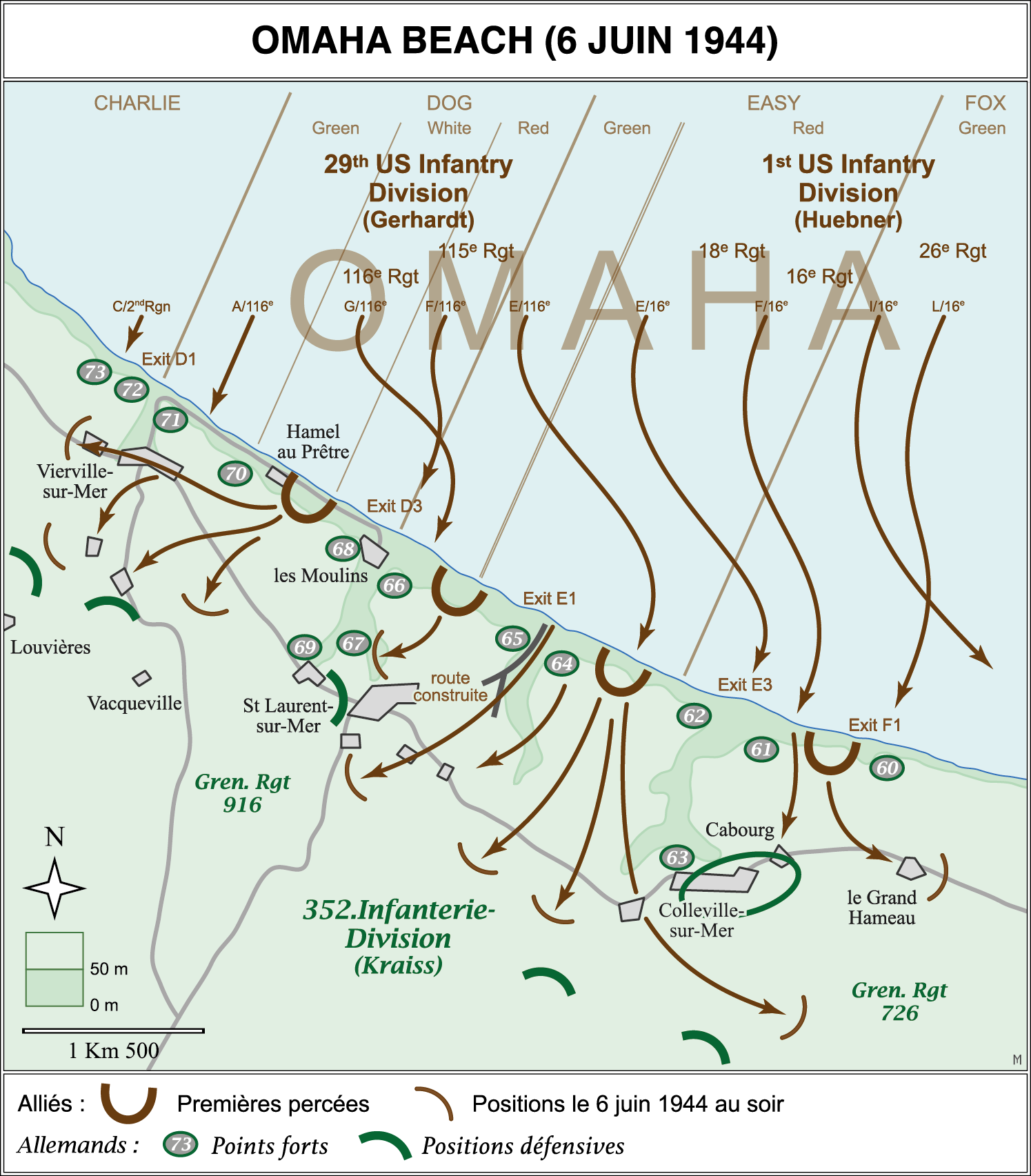

The American Beaches

- Omaha Beach -

Omaha Beach, named after a town in Nebraska, covered six kilometres of coast and the villages of Vierville, Saint Laurent-sur-Mer and Colleville. This sector was situated between Utah Beach, the second American beach and the British sector Gold. At the entrance to the valleys leading to the beach, the Germans had established 14 strong points complete with anti-tank walls and ditches, machine gun and mortar positions, mine fields and barbed wire. In order to destroy this defensive system, manned by 352nd Infantry Division which had arrived as reinforcements in April 1944, the Allies had planned to bomb the positions at night and shell the coast at dawn. Two divisions would land on this beach 1st and 29th Infantry Divisions commanded by Generals Heubner and Gerhardt. The mission for the force was to establish a 30 kilometres bridgehead between Utah Beach and Gold Beach and advance towards Saint-Lô.

The Preliminary Bombardment

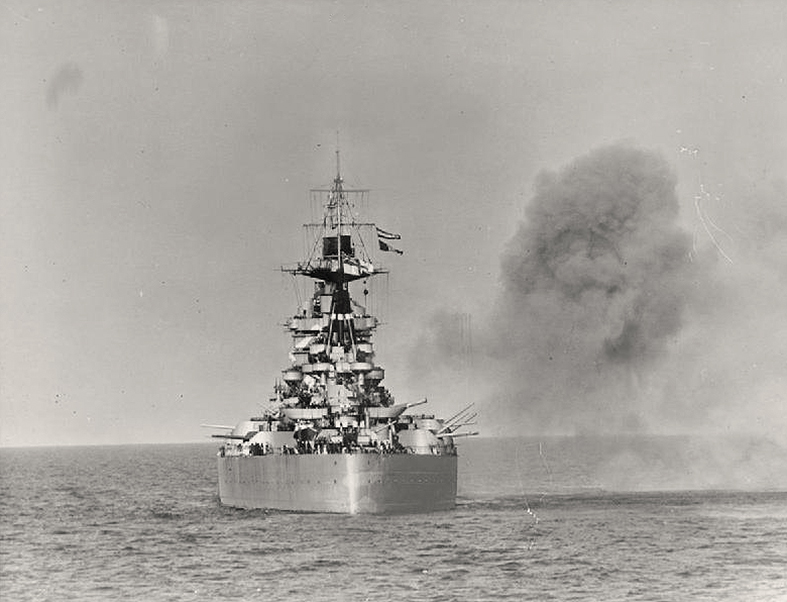

Prior to the landings, the air force and navy would bomb and shell the Omaha sector for 45 minutes.

The action commenced at 0300 hours when the flagship, the USS Ancon, dropped anchor, in high seas and strong currents, 23 kilometres from the coast. At 0430 hours, the troops commenced embarking in the landing craft. While at 0545 hours, the battleships Texas and Arkansas, the cruisers Glasgow, Georges Leygues and Montcalm, two French vessels, and eleven escort destroyers opened fire on the German gun batteries and notably on the battery at Longues-sur-Mer.

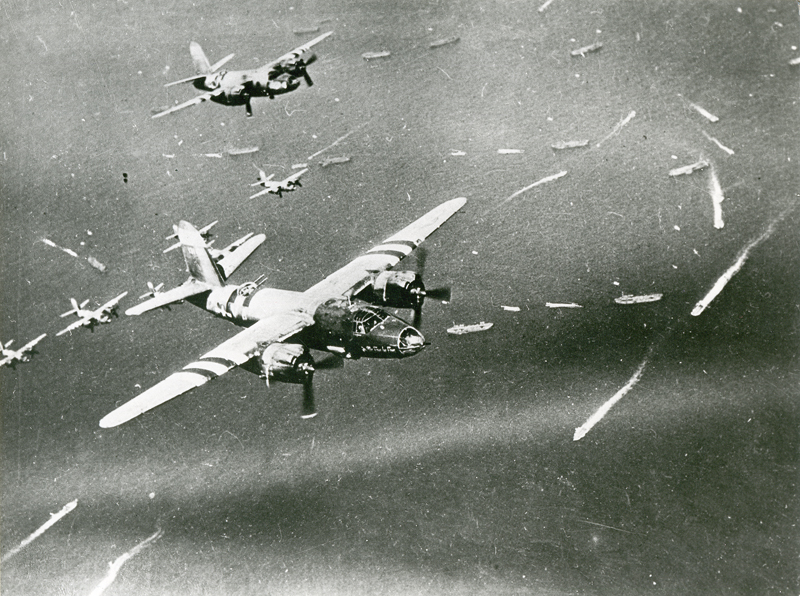

At 0600 hours, the air force followed the naval bombardment, 329 Liberator aircraft of the 8th US Air Force, protected by 36 squadrons of Mustang and Spitfire aircraft, flew over the coast dropping 13,000 tons of bombs. Flying high above the clouds and in fear of hitting the troops approaching the coast, the aircraft dropped their bomb loads far inland with no destruction to the German fortifications.

As the troops treaded the sand of Omaha, the German defensive system was intact and capable of repulsing an American assault.

The First Wave

At 0630 hours, the assault force of 1st Division (the Big Red One) and 29th Infantry Division landed on sectors Charlie, Dog, Easy and Fox. In the centre of Easy Sector, the photographer Robert Capa took his iconic images. Strong currents carried units far from their designated sectors.

A total of 1,450 men, composed of eight companies of 116th and 16th Regiments, were the vanguard of the assaulting forces. While the still intact German coastal batteries opened fire, awaiting them, high above the beach, were the well-established units of 352nd Infantry Division commanded by General Kraiss.

As soon as A Company of 116th Regiment stepped ashore, on the right flank of the assaulting forces, it was annihilated. The regiment lost 1,000 men in a few minutes. The terrible enfilading fire cut down the Americans on the various sectors of the beach. Two companies were holed up at Les Moulins, four other companies on the heights at Colleville, and another drifted so far from its sector that it took 90 minutes before it could even land. The situation was exacerbated when 35 amphibious tanks out of 83 launched in the first wave, sank or were destroyed before reaching the shore. Those tanks which did land on the beach were destroyed by gun fire. After 30 minutes, some of the men had managed to reach the pebble embankment at the top of the beach. It was during this chaos, when the first wave was still attempting to leave the shoreline that the second wave arrived at 0700 hours.

The Second Wave

As planned, the second assault wave of 29th Division landed at 0700 hours, followed 30 minutes later by units of 1st Division. On the beach, with a rising tide, chaos was total, men in a state of shock were incapable of advancing and losses were increasing minute by minute.

At 0800 hours, elements of 16th Regiment had established themselves behind the bank overlooking the beach. The regiment of “The Big Red One” outflanked the German strongpoint WN60 and seized it an hour later and headed towards Le Grand Hameau. It was at this point that the first valley was cleared of German forces at 0900 hours. It was in this sector that Colonel George Taylor of 16th Infantry Regiment called to his men with the words, later to become famous, “there are two types of men on this beach those that are dead and those that are about to die. Let’s get the hell of this beach!”

Simultaneously, other units of 16th Regiment, which had landed on Easy Red, crossed the embankment hidden from the German fire between WN 65 and 64.

Further to the west at Vierville, 500 men of 116th Regiment and 5th Ranger Battalion scaled the cliffs to reach the plateau; it was one of the first advances inland. An hour later, 600 men led by General Cota, deputy commander of 29th Division, regrouped and advanced towards Vierville which was reached at 1100 hours.

At 0900 hours, 2nd and 3rd Battalions of 116th Regiment had scaled the high ground between WN65 and WN66. Opposing them were troops of 352nd Infantry Division who continued to resist even though their fire had diminished in intensity.

Several hours after H-Hour, a bridgehead was slowly, and with difficulty, established at the very moment when General Bradley commander of the land forces was considering abandoning Omaha.

General Bradley, aboard the heavy cruiser USS Augusta, followed the battle at Omaha. As head of the American land forces he was aware minute by minute of the assault and the situation on the beach. The news was grave; Bradley’s forces were being massacred on Omaha. Due to the alarming news and the inability of the troops to advance forward off the beach, General Bradley, at 0900 hours, considered re-embarking his forces and landing them on the sectors Gold and Utah but, with the risk of leaving a huge gap in the Allied bridgehead. However, the situation improved at 0930 hours, Bradley had received a message that the troops, until then pinned down on the beach, had advanced in the Easy Green, Easy Red and Fox Red sectors, to reach the high ground overlooking the beach. The request to withdraw from the beach was never sent to Eisenhower. Reinforcements disembarking at 1030 hours finally pushed the balance in the Americans favor.

The Liberation of Vierville, Colleville and Saint-Laurent

The centre of Vierville was reached at 1100 hours and finally liberated at midday by units of 116th Infantry Regiment. The strong points WN65 and WN64 were also neutralised at midday allowing access to the exit at the Ruquet Valley. Simultaneously, GIs entering to the west of the village of Colleville met heavy resistance from units of 352nd Division which were holding the town centre. The village was only completely liberated the following morning. Reinforcements from 115th Regiment entered Saint-Laurent in the afternoon but the town was not completely cleared of German resistance until the following day.

Assessment of 6th June

By the evening of 6th June, the German 352nd Division had sustained losses of 1,200 men, 200 killed, 500 wounded and 500 missing in action.

The situation for the American forces was tenuous. Despite 34,250 men and 2,870 vehicles having landed on 6th June, the advance inland for the American forces remained difficult against stubborn resistance from several of the German strong points. The exits were not large enough to enable the troops to advance inland without difficulty. By 1400 hours, however, three exits were open D1 at Vierville, E3 near strong point WN62 at Colleville and F1 near WN60. The losses sustained by the American forces were heavy, 3,900 men of which 1,000 had been killed while establishing this fragile bridgehead, eight kilometres in length and two to three kilometres in depth rather than the planned 25 kilometres front with a depth of eight to ten kilometres.

Robert Capa, a Photographer at the Centre of the Assault

Robert Capa, aged 30, landed on Omaha as a photographer for Life Magazine. He was a veteran photographer of the Sino-Japanese and Spanish Civil Wars. On D-Day, Capa was the only photographer to have been authorized to land in the first wave, in the sector Easy Red. In order to seize this historic moment he carried three cameras. Short of film and deeply shocked, Capa re-embarked aboard a hospital ship taking the time to note his reels of film. On arrival at Weymouth, Capa chose to return to Normandy immediately and handed over his films to a Life courier. The films arrived in London in time for the day’s edition. The development was carried out in hast and only eleven blurred images could be developed. Capa returned to Normandy on 8th June and continued to cover the Battle of Normandy. Ten years later, Capa was killed on 25th May 1954 when he stepped on a mine while covering the war alongside the French Army in Indochina.

The American Beaches

- Utah Beach -

In order to rapidly capture the port of Cherbourg, indispensable for the arrival of the logistics, the Allied High Command in December 1943, added an additional landing beach to the west of La Baie des Veys. Named after an American state, the sector of Utah extended from Sainte-Marie-du-Mont to Quinéville. General Barton’s 4th Infantry Division was given the task of landing here at Saint-Martin-de-Varreville. This huge beach was ideal for an amphibious landing despite the hinterland being composed of marshland three kilometres in depth. Once ashore and the bridgehead secured, 23,000 GI’s had to establish a junction with the airborne troops which had landed several hours earlier in the Sainte-Mère-Eglise and Sainte-Marie-du-Mont sectors.

The Coastal Bombardment

One hour after the arrival of the parachutists, the Force “U” flagship, USS Bayfield, dropped anchor at 0230 hours, 20 kms from the coast along with 800 war and merchant ships.

The assault was preceded at 0545 hours by an intense naval bombardment. The battleship USS Nevada, opened fire on the powerful German batteries at Azeville and Saint-Marcouf while the cruiser USS Tuscaloosa concentrated its fire on Mont Coquerel and Crisbecq-Saint-Marcouf.

Minutes before the arrival of the landing craft, 276 Marauder bombers of the US 9th Air Force bombed the German positions. WN5 was totally destroyed. At 0600 hours, six Douglas Boston aircraft of 342nd Lorraine Squadron, with French crews, laid a smoke screen between the islands of Saint Marcouf and Barfleur to inhibit accurate German artillery fire. The batteries however caused some damage to the American fleet, sinking several ships. Amongst them, the USS Corry which hit a mine and was struck, at 0630 hours, by German fire from the Crisbecq battery, sinking an hour later. Of the 284 crew, 22 men lost their lives that morning.

Frenchmen over Utah Beach

Established in the Levant in 1941, the Lorraine Bomber Group operated for the first time against Axis forces in Cyrenaica. This unit of the Free French Forces later served in Great Britain flying Douglas Boston medium bombers. Attached to the RAF in April 1943 as 342 Squadron, the Lorraine Group carried out missions in June 1943 against the V1 launch sites in France and Belgium. By the spring of 1944, the squadron specialised in night bombing but, on D-Day, was designated by the High Command to lay a smoke screen between Barfleur and the Vire estuary. On 6th June 1944, 12 Boston aircraft took off to carry out their mission over Utah.

The group continued to serve during the Battle of Normandy destroying bridges over the River Seine, and later participated at Arnhem, over the Ardennes and during the Rhine Crossing. The unit was given the title of “Compagnon de la Libération” by General de Gaulle in May 1945.

The First Wave

The first assault wave on Utah landed between 0640 hours and 0650 hours. Supported by amphibious tanks of 70th Tank Battalion, 28 of 32 tanks released three kms off the coast reached the beach and three battalions of 8th Regimental Combat Team, 4th Infantry Division, landed one kilometre to the south of their initial landing zone. Among the 600 men who regrouped were General Theodore Roosevelt, deputy commander of the division and the only general to have landed in a first assault wave. After having realised the landing error, strong currents had carried his force from its planned landing zone, Roosevelt chose to land the reinforcements at a position where the German defenses happened to be less redoubtable but, at the risk of a great deal of congestion. Towards 0800 hours, the entire 8th Regiment had landed and made its way towards Pouppeville. The long awaited junction with the parachutists of 101st Airborne took place at Pouppeville at 1300 hours.

The son of a former President of the United States and distant cousin of Franklin Roosevelt, President since 1932, Theodore Roosevelt was 57 years old when he landed on Utah Beach on 6th June 1944. Roosevelt was twice wounded during the First World War and served for part of the Second World War as a colonel. He was promoted to general in 1941, and participated in the landings in North Africa before serving as deputy commander of 4th Infantry Division. Despite his frail health and advanced age, he convinced the commanding general of 4th Division to allow him to land in the first assault wave on Utah Beach. Roosevelt died of a heart attack at Carentan on 12th July 1944 prior to taking command of 90th Infantry Division. General Roosevelt lays today at the American cemetery at Saint-Laurent.

The Arrival of the Second and Third Waves

The 2nd assault wave landed at 1000 hours with the arrival of 22nd Regiment, which had the mission of advancing north towards Saint-German-de-Varreville and Saint-Martin-de-Varreville while one battalion advanced along the coast. Constrained to cross the flooded zone, the other two battalions took more than seven hours to reach Saint-Martin and Saint-Germain. The 3rd Battalion, which had captured WN10, advanced no further than the Hamel de Crouttes by evening.

At midday, the third assault wave landed on the beach at La Madeleine. The 12th Infantry Regiment was accompanied by 40th Cavalry group, a unit of engineers and two battalions from 359th Infantry Regiment of 90th Infantry Division.

Due to the congestion at the exits, 12th Regiment was obliged to cross the flooded zone south of Beuzeville-au-Plain where it established its positions on the left flank of 502nd Regiment, 101st Airborne, by the end of the day.

Assesment of 6th June

By the evening of 6th June, the infantry of 4th Division had extended the bridgehead to the Hamel aux Cruttes, Beuzeville-au-Plain, Turqueville, to the south of Saint-Mère-Eglise, Blosville and Sainte-Marie-du-Mont. Beyond these positions, only the junction with the paras at Pouppeville had been established. German forces from 91 Luftlande and 709th Infantry Divisions strongly resisted the American forces. By the evening of 6th June, 23,000 men and 1,700 vehicles had landed on Utah Beach. The 4th Division’s losses were 200 men killed of which 60 of them were at sea. The landing error was beneficial in that it distanced the forces from the heavy gun batteries at Crisbecq and Azeville.

The American Beaches

- La Pointe du Hoc -

At the summit of La Pointe du Hoc, a 30 metres high natural promontory dominating a pebble beach, the German Forces had installed, in 1942, a heavy battery capable of firing on a large part of the landing coast. In 1944, six French guns of 155mm caliber, with a range of 18 kms, had been installed; the guns were directed by an observation post which had been constructed in 1943. The garrison consisted of 200 men, composed of gunners and infantry to defend this fortified site.

The seizing of the battery by Allied forces was vital for a successful landing on Omaha and Utah Beaches.

The gun position had been bombed in April, May and June 1944. However, an assault force from the sea scaling the cliffs with ropes and ladders was also considered necessary. Colonel Rudders, 2n Ranger Battalion, attached to 116th Regiment of 29th Division was given this hazardous mission.

Approaching La Pointe du Hoc

At 0500 hours, the Cruiser HMS Glasgow and the battleship USS Texas were positioned off the coast of la Pointe du Hoc to support the Ranger assault. The guns of the Texas fired 255 rounds on the German positions before turning its fire on Vierville. Towards 0550 hours, the destroyers USS Saterlee and HMS Talybont opened fire on la Pointe du Hoc. Finally, at 0600 hours, bombers of 9th Air Force bombed the German positions between Utah and Omaha Beach. Simultaneously, three companies of Rangers boarded their LCAs and DUKWS. As they advanced towards the objective, Rudder realised that there had been a navigational error and the force was heading to another promontory further to the east at la Pointe de la Percée. Rudder ordered the craft to sail parallel with the coast under enemy fire and the Rangers finally arrived at the base of the cliffs 40 minutes later than the initial planned schedule. Colonel Rudder and his men found themselves alone as the reinforcements from 5th Battalion had been diverted to Omaha at 0700 hours.

The Assault at La Pointe du Hoc

Under German gun fire, the Rangers fired their ropes with rockets and installed rope ladders to the side of the cliffs, along with telescopic and fire brigade ladders. The 225 Rangers started to the climb at 0710 hours. Ten minutes later, the rangers of D, E, and F companies had scaled the cliffs and were engaged in fighting the garrison. Within 15 minutes, the Rangers had seized the battery but found no guns in the emplacements, wooden poles had been installed in their place. The guns had been removed in April 1944, following a bombardment, to positions 1.5 kms inland. The guns were discovered in a sunken lane by Sergeants Lomell and Kuhn, at 0900 hours, and were subsequently destroyed.

La Pointe du Hoc had been seized by the Rangers but they were isolated, surrounded by German troops of 352nd and 716th Divisions. The casualties were heavy, 135 Rangers were lost during the assault. By the evening of 6th June, 116th Regiment, due to relieve the Rangers, was six kms away at Vierville. It was only at 2100 hours that Rudder received a small detachment of 23 Rangers from 5th Battalion. However, the 90 surviving Rangers were only finally relieved on 8th June.

ENT.2-40

Colonel James Rudder was not the typical American officer. Before taking command of 2nd Ranger Battalion in June 1943 “Big Jim” had been an American football coach in his home town of Brady, Texas. Rudder was a farmer by profession and served in the Army Reserve. He was also an accomplished sportsman who had been called up for active service in 1941 at 31 years of age.

His moment of glory, despite several wounds, was the assault at la Pointe du Hoc. For outstanding bravery, he was decorated with the Distinguished Service Cross. In January 1945, Rudder commanded 109th Infantry Regiment during the battle in the Ardennes. He was promoted to brigadier general in 1954 and retired in 1957 as a major general. Rudder died on 23 March 1970 at Houston Texas.

Leonard Lomell, the other hero of La Pointe du Hoc

Sergeant Leonard Lomell was 24 years of age on D-Day. He commanded a section of D Company of 2nd Ranger Battalion led by James Rudder. Despite being wounded on the beach, he was one of the first Rangers to scale the cliffs. The destruction of the guns had been his mission but, he was stunned to discover the absence of any guns. The company’s subsequent mission was to establish positions on the coastal road and Lomell and Sergeant Jack Kuhn went ahead on reconnaissance, discovering the five guns in a sunken lane. Using thermite charges, which melted the guns mechanisms, Lomell and Kuhn neutralised two of the guns. The gun sites on the three others were destroyed. Lomell further distinguished himself in December 1944, at Hill 400 in the Heurtegan Forest in Germany, for which he was decorated with the Silver Star. Leonard Lomell died in 2011.

The British Beaches

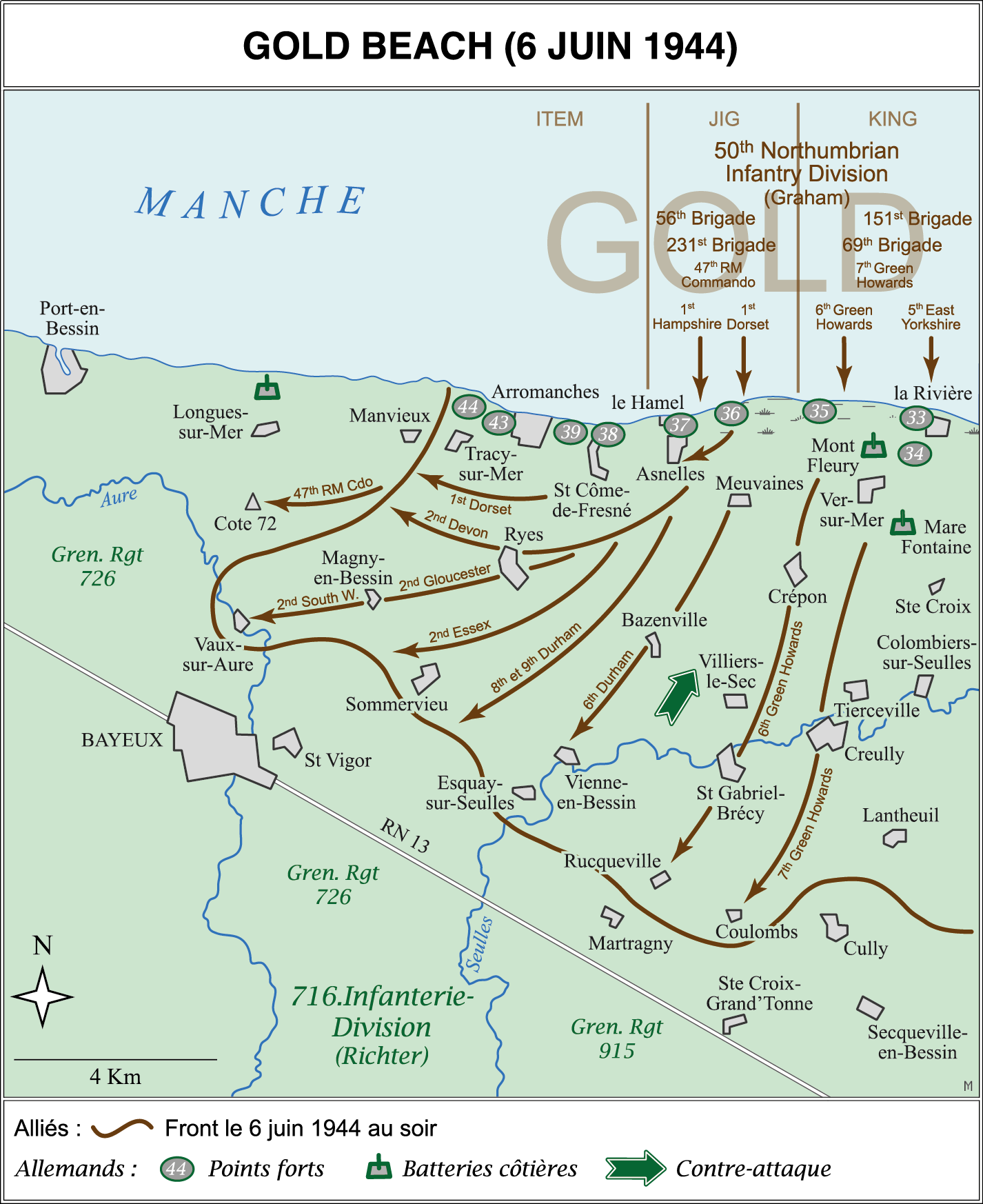

- Gold Beach -

The Gold Beach Sector, situated between the American Omaha Beach and the Canadian Juno Beach, extended from Port-en-Bessin to Ver-sur-Mer and was under the command of the British 30th Corps. The 50th Infantry Division (50th Northumbrian Infantry Division) commanded by General Graham, which landed to the east of Arromanches between Asnelles and Ver-sur-Mer, had the mission of forming a junction with the American and Canadian forces and of advancing to the main highway which linked Caen and Bayeux and to seize the town of Bayeux.

Between Arromanches and Port-en-Bessin, the Longues-sur-Mer gun battery posed a serious threat to this sector of the coast. The Allies carried out a bombing mission, 99 four engine aircraft dropped 604 tons of bombs on the battery. At 0510 hours, the cruisers Belfast, Orion, Ajax, Argonaut and Emerald opened fire on the batteries at Longues-sur-Mer and Vaux-sur-Aure. Despite the bombing, the Longues battery was still capable of firing.

Between 0605 and 0620 hours, the guns opened fire on the American fleet off Omaha Beach and on Gold Beach forcing HMS Bulolo (the headquarters ship for the Gold sector) to weigh anchor. Following a duel between the battery and the battleship Arkansas, the cruiser Ajax and the French ships, Montcalm and Georges Leygues, the landing phase could commence.

The First Assault Wave

At 0725 hours, the first wave of 50th Division (231st and 69th Infantry Brigades) landed on Jig sector (Asnelles) and King sector (Ver-sur-Mer) accompanied by assault tanks of 79th Division which were vital in making a breach and silencing the strong points.

On King sector, 5th East Yorkshire (69th Brigade) landed at La Rivière and immediately came under fire from an 88mm gun in the WN33 strong point.

The Green Howards (69th Brigade) in its sector rapidly took the WN35 strong point at the Hable-de-Heurtot before heading towards the Mont Fleury battery, further inland from the beach. The gun crew here surrendered without a fight after having been badly shaken by the fire from the Orion.

For his actions during this assault, Sergeant-Major Stanley Hollis was decorated with the Victoria Cross, the only VC to have been awarded on D-Day.

The 231st Brigade landed without difficulty on Jig sector before the advanced stalled in front of the WN37 strongpoint in the village of du Hamel.

The 7th Green Howards (69th Brigade) had advanced to La Riviere by 0830 hours, liberating Ver-sur-Mer which had been abandoned by the German forces. The British took the Battery at la Mare Fontaine without a fight, the German troops being too shocked to react due to the shelling from the Belfast.

Shortly before 0825 hours, 47 Royal Marine Commando landed at Asnelles with the objective of liberating Port-en-Bessin. Delayed due to the congestion on the beach and stiff resistance at Le Hamel, the commandos took time to assemble, only beginning their advance at 1400 hours and reaching Port-en-Bessin the following day.

Of all the German coastal gun batteries in this sector, only the battery at Longues-sur-Mer opened fire on the assaulting forces. Two direct hits by the cruiser HMS Ajax at 0845 hours, however, temporarily put the battery out of action.

Stanley Hollis was 32 years of age when he landed on Gold Beach on 6th June 1944. He had enrolled in 4th Battalion Green Howards in 1939. On the outbreak of war, he was mobilized and served in 6th Battalion of the same regiment. He participated in the campaign in France in 1940 with the British Expeditionary Corps and subsequently served in the 8th Army in North Africa at El Alamein and Tunis before seeing combat in Italy where he received his first wound. Hollis rejoined the Green Howards and landed with his battalion on Gold Beach. Situated inland from the beach was the Mont Fleury gun battery, composed of four guns of 122 mm calibre, which had been put out of action by Allied bombardment without firing a shot. However, 6th Green Howards had been given the mission of destroying the guns. Sergeant Hollis led the attack capturing or killing the troops of the German garrison. Later, in the village of Crepon, Hollis’ company met stiff resistance in the town centre. Hollis successfully rescued two of his comrades who were pinned down by enemy fire. For his double act of bravery on the same day, Stanley Hollis was decorated by King George VI with the Victoria Cross, the only D-Day soldier to have received the medal for his actions that day. Stanley Hollis died in England in 1972.

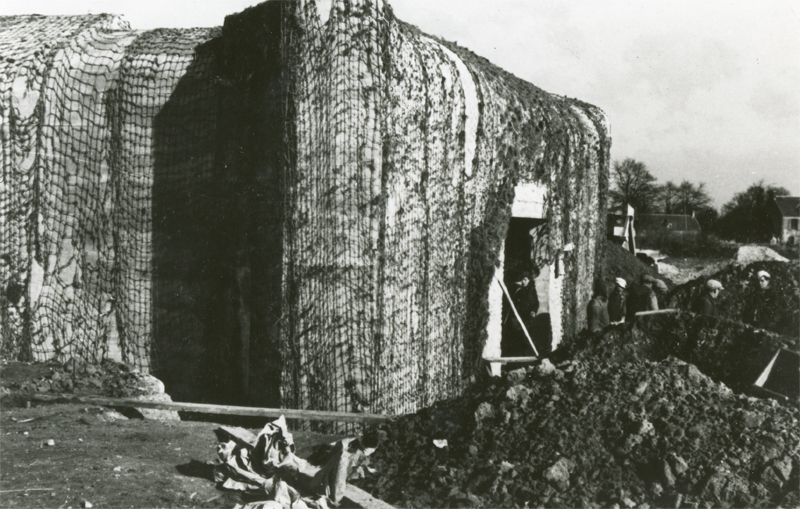

The Battery of Longues-sur-Mer, a Vital Element in the German Defences

The Naval gun battery at Longues-sur-Mer, composed of four 150 mm guns with a range of 20 kms and an observation post, situated above the cliffs, was bombed by the Allied air force, without success, on 6th June 1944. The battery posed a threat to the British infantry landing on Gold Beach but, its effectiveness would have been even greater if the construction of the observation post had been completed by 6th June 1944. In front of the main aperture was earth which had been excavated during the construction and which had been used to help camouflage the edifice. The Allied air force had considerably slowed up the construction of the building notably just prior to the landings. Despite this handicap, the German gunners fired on their naval counterparts for much of 6th June until two direct hits from the Georges Leygues put the battery out of action. When the British forces arrived at the site the following day, only casemate 1 was intact, the others were partially or completely destroyed.

The Second Assault Wave

The 50th Division’s 2nd assault force arrived at 1100 hours, 151st and 56th Infantry Brigades landed and advanced towards Bayeux. Magny, Vaux-sur -Aure and Bayeux were reached in the evening.

Towards midday, B Company of 1st Hampshire (231st Brigade) entered Asnelles after having encountered serious resistance from the battery at Le Hamel (WN37). Following the liberation of Asnelles, the fortification was outflanked from the south. The assault began at 1400 hours and was carried out from all directions, the battalion lost four commanding officers over the day, three of them were killed or wounded. The battery at Le Hamel, which had resisted naval and air bombardment, finally fell at 1600 hours.

The town of Arromanches was taken in the evening by units of 1st Hampshire. The village of Ryes was liberated by 2nd Devonshire Regiment (231st Brigade) after several hours of combat with 716th Infantry Division. The village of Crepon was liberated by D Company of 6th Green Howards (69th Brigade).

Everywhere, the Germans withdrew but, they were also capable of counter- attacking. An assault group led by Kurt Meyer attacked between Villiers-le-Sec and Bazenville. The assault was intended to repel the forces landing on Gold Beach. The German offensive was called off in the afternoon but it had forced the British troops to withdraw in the evening to Saint-Gabriel-Brécy.

Assessment of 6th June

The objective of 69th Brigade was reached in the evening, the Caen-Bayeux Highway (RN13). Simultaneously, elements of 51st Highland Division landed on Gold Beach along with 7th British Armoured Division. The junction with the Canadian forces was made by 7th Green Howards in the village of Tierceville at the end of the day.

On the evening of 6th June 1944, the British had landed 25,000 men on Gold with 400 casualties. A bridgehead of ten square kilometres had been formed and the highway had been reached as planned. But Bayeux and Port-en-Bessin were still in German hands and the junction with the American forces had not yet been established.

The British Beaches

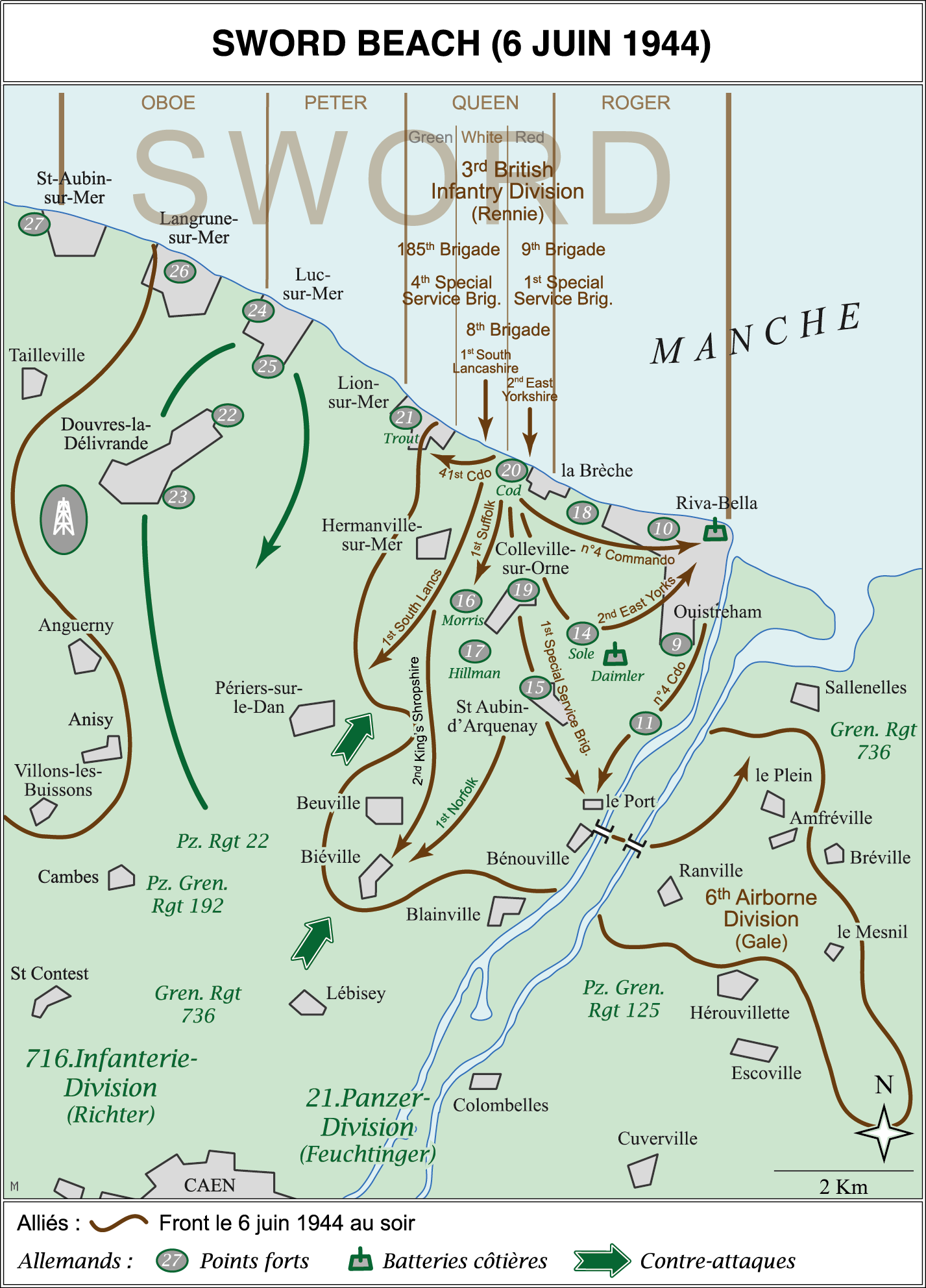

- Sword Beach -

Along with Utah, Sword was the other beach which was added to the initial plan in December 1943. Sword extended from Langrune to Ouistreham. However, the Allies chose to concentrate the forces on a narrower front at Hermanville and Colleville-sur-Orne. The 3rd British Division would lead the assault followed by specialized assault and amphibious tanks. The flanks would be protected by two commando brigades, 1st Brigade was to seize the battery at Ouistreham and 4th Brigade would liberate Lion-sur-Mer and Luc-sur-Mer. The 185th Brigade of 3rd Division was to take advantage of the situation and advance to Caen before nightfall. Finally, General Rennie’s division was to make the junction with the Canadian forces.

Bombardment and Artillery Fire

The fleet positioned off Sword Beach opened fire at 0500 hours. Tragedy struck 30 minutes later when the Norwegian destroyer Svenner was cut in two by a German torpedo. Hit in the engine room, the Svenner sank within minutes, 33 sailors, including many Norwegians and one British sailor, were lost, 185 survivors were recovered from the sea. The naval bombardment of Ouistreham continued at 0545 hours with fire from HMS Scylla, while the batteries to the east of the Dives were shelled by the Warspite, the Ramilles and the Roberts.

At Sword, the deluge of fire on the coastal defenses was enormous. The guns of Frobisher, Dragon, Danae, Arethusa and Mauritius progressively stopped firing to allow the assault forces to land.

2.50

The Norwegians on D-Day

The Svenner was not the original name of the ship. The S class destroyer was launched on 1st June 1943 as HMS Shark but, on 6th June, the Svenner was flying the Norwegian flag as part of the Allied armada.

The Norwegian naval force consisted of three fast patrol boats, three corvettes and, in addition to Svenner, two other destroyers of British origin, the Glaisdale and the Stord. On 6th June, hidden by a smoke screen, two German torpedo boats of 5th Flotilla, based at Le Havre, discovered the Allied Fleet. The Svenner was hit by one of the 18 torpedoes launched by the Kriegsmarine. The tragedy of the Svenner in no away undermines the feat of arms of the other Norwegian units involved in Operation Overlord, at sea and in the air.

Air force squadrons, 331st and 332nd of 132nd Wing were attached to the Canadian Air Force supplying vital air to ground support for the Canadian and British infantry.

The First Assault Wave

At 0720 hours, specialized units of General Hobart’s 79th Division landed and cleared the beach obstacles. Flail tanks, to clear mines, were the first to land followed by special tanks of 13th/18th Hussars.

The first troops of 3rd Division landed at 0725 hours on Queen Beach, in the sub sectors Red and White, opposite Colleville-sur-Orne and Hermanville-sur-Mer. The 8th Infantry Brigade and its battalions 2nd East Yorkshire and 1st South Lancashire and Lord Lovat’s 1st Special Service Brigade including 1st French Commando Battalion commanded by Commandant Kieffer.

In the seaside resort sector of Colleville, the 2nd East Yorks were confronted with the German strong point codenamed “Cod” losing 200 men in the combat. Troops of the South Lancs liberated La Breche d’Hermanville with few loses. Cod finally fell to the South Lancs at 0900 hours.

The Royal Marine 41 Commando (4th Commando Brigade) landed to the west on Sword, liberating Lion-sur-Mer and making the liaison with 48 Royal Marine Commando which had landed on Juno Beach. The commando advance however was stalled at Lion-sur-Mer by the German strongpoint WN21. Lacking radio communications, the commando was unable to request naval gun fire support and sustained heavy losses during this assault. WN21, codenamed “Trout”, was finally liberated the following day.

ENT.2-52

Simon Fraser Lovat, 25th Chief of the Fraser clan and 17th Lord Lovat was born in 1911 and volunteered for the commandos in 1940. He participated in the landings in Norway, on the Lofoten Islands in March 1941 and during the raid at Dieppe in August 1942, as a lieutenant colonel leading N°4 Commando. On 6th June 1944, Lord Lovat commanded the recently formed 1st Special Service Brigade leading it ashore at Colleville wearing suede trousers and a roll neck sweater and carrying a rifle, his personal piper, Bill Millin, at his side. As planned and only several minutes late, he established the junction with Major Howard’s men at Bénouville Bridge before advancing into the center of the British bridgehead.

Gravely wounded on 12th June by artillery fire from 51st British Division during the combat at Bréville, he was evacuated to England. After the war, Winston Churchill appointed him Under-Secretary of State at the Foreign Office. Lovat retired from the army in 1962 with the rank of brigadier, and was involved in politics in the House of Lords and in his home county of Inverness. Lord Lovat died at Beauly in Scotland in 1995.

The First Breakout and Liberation

At 0845 hours, Lord Lovat, his piper and the men of 1st Special Service Brigade disembarked.

Hermanville-sur-Mer was liberated by 1st South Lancashire Battalion (8th Brigade) at 0930 hours which then continued to advance before being halted by 88mm gunfire on the ridge near Périers. The village became the assembly point for the second echelon troops.

Simultaneously, 1st Suffolk Battalion (8th Brigade) liberated Colleville-sur-Orne and advanced towards the “Morris” strong point, on the Saint-Aubin-d’Arquenay road, which surrendered without a fight.

The fortified position at Riva-Bella composed of the casino, the port and locks was rapidly reached by Lord Lovat’s commandos. The French force, “Commando Kieffer” with the help of a British tank, neutralised the strong point at the casino shortly before 0900 hours. The German garrison surrendered several minutes later to the British forces while the French regrouped and set out towards Saint-Aubin-d’Arquenay and Bénouville. Ouistreham-Riva Bella was completed liberated by midday.

Commando Kieffer’s assault on Ouistreham

For the majority of the 177 men serving in the Commando Kieffer, the landing was their baptism of fire, although several had served in this battalion of the Free French Forces from its formation in 1942 and had already participated in several raids along the enemy coast. The Commando Kieffer was attached to the Franco-British N° 4 Commando commanded by Colonel Dawson, which was integrated into Lord Lovat’s brigade, along with N°s 3 and 6 Commandos and 45 Royal Marine Commando. Commando Kieffer had the honour of being the first unit to land at Colleville. Three men were killed on the beach before the assault on the casino at Ouistreham which began shortly before 0900 hours. Twenty minutes later, Kieffer and his men, with the help of a tank, neutralized the German position situated in the cellars of the edifice. This feat of arms came at a heavy price; seven men were killed during the morning in the seaside town. The second part of the mission was to make the junction with the airborne forces at Bénouville, which was carried out successfully at 1600 hours. Early evening, the French commando force had carried out its third mission, to establish defensive positions on the heights at Amfreville to the east of the Orne in order to consolidate the British bridgehead. Kieffer, who had himself been wounded twice, lost 44 men of which ten had been killed. The French held this sector of the bridgehead until mid-August before pursuing the German retreat in the direction of the Seine in Operation Paddle. By the time Kieffer’s force had left Normandy, on 5th September 1944, it had been reduced to 95 men. After resting in England, the force participated in a second amphibious operation in Holland on 1st November 1944.

Closing the access to Caen

Despite operations on the beach and in the airborne sector having been successful, the progression in land was not as easy.

In the afternoon, 185th Brigade’s advance was halted by 21st Panzer Division at Biéville-Beuville. At 1900 hours, the situation for the British became critical when a company of assault grenadiers of 21st Panzer attacked from Mathieu (8kms from the coast) crossing Douvres-la-Delivrande and taking advantage of a five kilometres gap between the Sword and Juno sectors at Luc-sur-Mer. At 2000 hours, the German column was forced to withdraw with the arrival of 250 gliders of 6th Airborne Division.

Isolated and constantly harassed, the German battle group withdrew to the Lebisey wood north of Caen at nightfall.

In the meantime, the German forces had abandoned several strong points which had resisted and slowed the British advance towards Caen. The strong point WN17, codenamed “Hillman”, which protected the headquarters of 736th Grenadier Regiment was taken in the evening by 1st Suffolks and amour of 13th/18th Hussars. While north of Saint-Aubin-d’Arquenay, the strong points “Daimler”, “Sole” and “Morris” fell later following assaults by 2nd East Yorks.

On 6th June 1944, General Feuchtinger’s 21st Panzer Division was the only German division present on the landing coast. Composed of 98 Panzer MK 4 tanks and 120 armoured cars, the division had a compliment of 16,000 men ready for combat in Normandy. However, indecision and prevarication on the part of the German High Command from the very start of the landings hindered the effectiveness of the armoured division. The first units in action were only effectively engaged at 0330 hours in an attempt to prevent the formation of the airborne bridgehead. Constrained to deploy the major part of his force between Caen and the sea, the possibility of implementing a major counter-attack, which Feuchtinger was counting on to repulse the British forces, was reduced hour by hour due to confused orders and counter orders from his superiors. The only counter-attack took place in the afternoon at Luc-sur-Mer before the forces involved made a hasty retreat. The one positive point for 21st Panzer was that by the evening of 6th June it had prevented access to Caen and continued to fend off the British offensives until the liberation of the west bank of Caen on 9th July 1944. During the Battle of Normandy, 21st Panzer sustained some of the heaviest losses of all German units engaged, 8,000 men were lost with more than half of them between 6th June and 31st July 1944.

Assessment of 6th June

In the afternoon, General Rennie’s forces had successfully repelled the only important counter-attack of D-Day carried out by 21st Panzer in the Périers sector.

Late on 6th June, the British forces made another attempt to pierce the enemy lines near Caen but, in vain. The 2nd Royal Warwickshire (185th Brigade) which had reached Blainville-sur-Orne at midnight was unable to advance further towards Caen due to 21st Panzer Division. By the evening of 6th June, the British had landed 29,000 men and 2,600 vehicles. Casualties were 600 men killed. But Caen, which should have been taken before nightfall, was still in German hands.

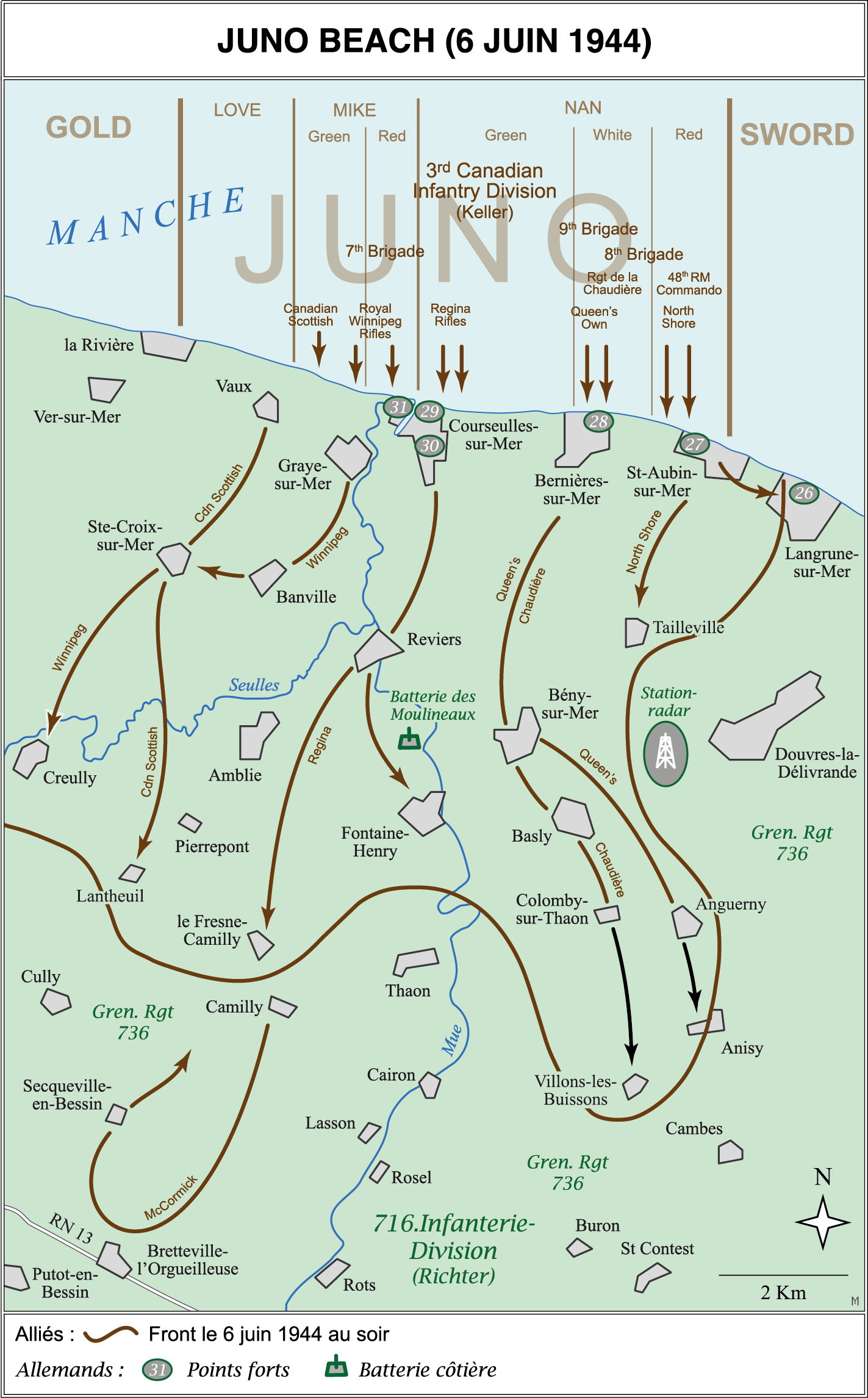

The Canadian Beach

- Juno Beach -

Situated between Sword and Gold, Juno extended between Graye-sur-Mer and Saint-Aubin-sur-Mer and was the domain of 3rd Canadian Infantry Division commanded by General Keller. The Canadians were supported, in the first wave, by 2nd Armoured Brigade and the British 48 Royal Marine Commando. The Canadian objective was to establish the junction with the British on Sword and Gold. The primary military objective was the airfield at Carpiquet to the west of Caen.

Prior to the landings at 0530 hours, the Cruiser Belfast shelled the German fortifications, notably the battery at Ver-sur-Mer. During one and a half hours, the German positions were bombarded by the navy and aircraft of the RAF.

The Canadians landed ten minutes later than the initial H-Hour and the forces on Sword and Gold. The stormy seas and reefs, which could only be crossed at high tide, led to the delay in the landings.

Major General Keller and the Canadians at Juno

Rodney Keller was born in England in 1900 of British immigrant parents; he volunteered for the Army and was educated at the Royal Military College at Kingston. Following his adopted country’s entry into the war, Keller took command in 1941 of Princess Patricia’s Light Infantry. In September 1942, Keller was promoted to Major General and took command of 3rd Canadian Infantry Division. He led his 18,000 men ashore onto Juno on 6th June 1944. Keller participated in the Battle of Normandy, notably the offensive to capture Caen and Operation Windsor, the liberation of the Capiquet airfield early in July. On 8th August between Caen and Falaise, he was severely wounded by American gun fire, during Operation Tractable, which compelled him to relinquish his command for the rest of the war. He was sidelined due to his language, strong temperament and an excessive consumption of alcohol. He retired in 1946. In 1954, following a heart attack, he died during a trip to Normandy.

The Canadians Land

At 0755 hours, despite the beach obstacles having been covered by the incoming tide, the first wave of 3rd Division (7th and 8th Infantry Brigades) landed over an eight kms front at Bernieres-sur-Mer, Courseulles-sur-Mer, Graye-sur-Mer and Saint-Aubin-sur-Mer.

The North Shore Regiment (8th Brigade) landed 20 minutes late at Saint-Aubin-sur-Mer directly in front of WN27 which was still intact despite the bombardment. With the help of the Fort Garry Horse and specialized assault tanks, which had landed at 0945 hours, the infantry out flanked this obstacle and liberated Saint-Aubin-sur-Mer at 1130 hours. The Regina Rifles Regiment (7th Brigade) landed at 0800 hours at Courseulles-sur-Mer opposite the WN29 strong point. Simultaneously at Graye-sur-Mer, the Royal Winnipeg Rifles and 1st Canadian Scottish landed and confronted WN31 but, without the planned armored support. At Bernières-sur-Mer, the Queens Own Rifles (8th Brigade) assaulted, also without armoured support, the strong point Cassine (WN28).

48 Royal Marine Commando

On the flank of Sword Beach at Saint-Aubin-sur-Mer, 48 Royal Marine Commando landed. On approaching the beach, two of the landing craft were sunk and only 50 % of the men landed on the beach. 48 Commando was part of Brigadier Leicester’s 4th Commando Brigade along with 41, 46 and 47 Royal Marine Commandos. Lieutenant Colonel Moulton’s 48 RMC advanced towards Langrune and Luc-sur-Mer to make the junction with 41 Royal Marine Commando which had landed on Sword Beach. Blocking the route was the redoubtable WN26 strong point. Despite the support of Centaur tanks, the British forces could not breach the German defenses due to stiff resistance and the arrival of 21st Panzer Division grenadiers at the end of the day. By the evening of 6th June, the commandos were unable to make the junction despite losing half of their effectives.

ENT.2-62.1

First Liberations